By Campbell Collins

“About suffering they were never wrong, / The Old Masters.”

I love these lines, the opening of W.H. Auden’s “Musée de Beaux Arts.” In the poem, Auden describes the paintings of the Brueghels, the Masters who understood suffering so well. He references their depictions of a Dutch Mary, head bowed beneath a blue robe, trudging ignored in the cold and almost hidden among the thronging crowds; mothers, contorted and heartbroken, collapsing into the stark-white snow that holds no relief; and Icarus’ pale, bare legs kicking desperately in an ignored corner of the sea, hardly more noticeable than the ice-capped mountains on the horizon. The Breughels, Auden tells us, understood how trivialities cloak suffering as “everything turns away / Quite leisurely from the disaster.” Families eat, children play, and “the dogs go on with their doggy life.” Perhaps the Low Country winters gave the Breughels a visual metaphor for the state of suffering: a blanket of snow, silent and innocent, that obscures dead and dying things beneath.

Perhaps the Low Country winters gave the Breughels a visual metaphor for the state of suffering: a blanket of snow, silent and innocent, that obscures dead and dying things beneath.

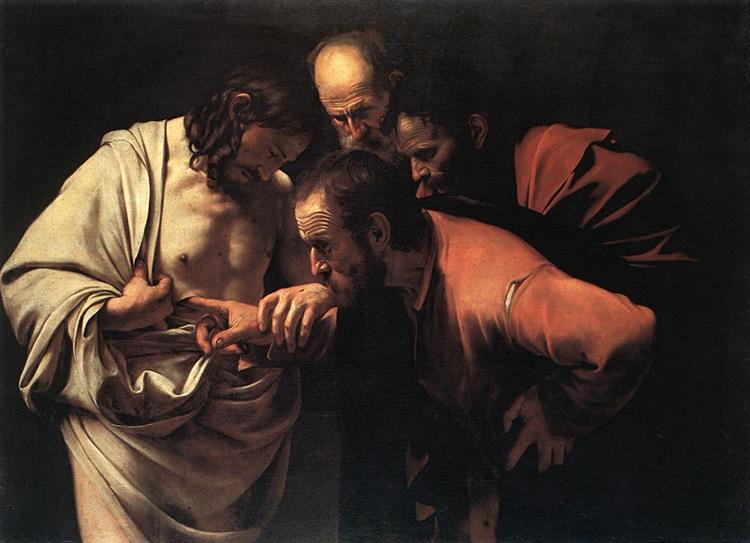

Yet when I seek to learn to suffer well—when I see the grown-up sorrows waiting just over the edge of my childhood and strive to know them as “light momentary affliction” that will prepare me for “an eternal weight of glory” (2 Corinthians 4:17)—I turn to Russia’s winters and the writing of Tolstoy, who saw not death but hope beneath the graying winter snow. In The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Tolstoy pokes and prods you until you become a sorry replacement for Christ in Caravaggio’s Incredulity of St. Thomas as a dubious Slavic jabs a grimy finger into your side.

Tolstoy’s story always carries me back to my family’s kitchen table, flipping through a brand-new copy of Perrine’s Literature until the line “‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘Ivan Ilyich has died!’” caught my attention. I read on, hunched over the pages with wrists throbbing under the book’s weight. At the beginning of his illness, Ivan muses, “Caius really was mortal, and it was right for him to die; but for me, little Vanya, Ivan Ilyich, with all my thoughts and emotions, it’s altogether a different matter. It cannot be that I ought to die. That would be too terrible.” At first I believed this realization was all Ivan had to teach. While death gained the upper hand over Ivan, I skimmed the ending of the story, haunted by Ivan’s pain. I closed the anthology and Ivan Ilyich’s three days of haunting, deathbed screams echoed in my head. Tolstoy sunk into me like a wet winter evening when the cold pools behind your eyes and down your throat. Death, Tolstoy, and the cold—they seem to clutch and grasp, insistent to touch every corner of our being. Ivan, as he realizes this, screams and screams.

Death, Tolstoy, and the cold—they seem to clutch and grasp, insistent to touch every corner of our being.

Yet, ultimately, this is not where Tolstoy leaves us. He tells us that, in Ivan’s final days, he “searched for his old habitual fear of death and didn’t find it.” Ivan asks, “Where is death? What death?” and finds that “there was no fear because there was no death. In place of death there was light.” In a story filled with darkness often more grotesque than tragic, Tolstoy allows hope to blaze in his final lines. We are not abandoned in the ache and the sorrow of the cold; instead, Tolstoy strides ahead of us, leaving muddy footprints in the snow that show us others have passed this way before. Ivan’s final words echo Christ: “‘Death is finished,’ he said to himself, ‘It is no more.’” With Ivan, we confront the final paradox of fallen human life: death comes and yet does not come as the warmth of Christ’s light overcomes death’s dark, wintry cold.

We are not abandoned in the ache and the sorrow of the cold; instead, Tolstoy strides ahead of us, leaving muddy footprints in the snow that show us others have passed this way before.

Luke tells a story in Acts 27:12: “And because the harbor was not suitable to spend the winter in, the majority decided to put out to sea from there, on the chance that somehow they could reach Phoenix, a harbor of Crete, facing both southwest and northwest, and spend the winter there.” Auden, the Brueghels, and Tolstoy show us sorrows that come as surely as the winter wind. Yet they remind us that we are not made to spend our soul’s winters under the weight of sorrow alone. Instead, they tell us that sorrow is not our permanent harbor and give us the hope to strike out and find a refuge from the winter in Christ as we await the coming springtime of His light.

Campbell Collins is a sophomore studying English and Religion.